Every European city has its own face. But not necessarily the new skyscrapers. Wooden architecture is what gives cities their distinctive character, even though few still boast an abundance of little trees. According to Milda Žekonytė, Head of Territorial Planning and Sustainable Environment at ID Vilnius, wooden architecture is no longer common in modern cities. “Until the beginning of the 20th century, wood was the cheapest and probably the easiest building material to obtain, which was particularly suitable for building houses in our climate. Until the middle of the 20th century, the majority of people in Lithuania lived in rural areas built with wooden huts, and only a small proportion lived in towns. Although we can think of timber construction as a traditional practice, over time, the more durable brick buildings began to dominate in the cities,” said Žekonytė. The Industrial Revolution and technological progress in society also contributed to this, she said. In Lithuania between the wars, there was even a plan to turn the whole country into a brick country by 2000, abandoning wooden architecture. But as systems changed, so did the plans. Indrė Užuotaitė, head of the Museum of Wooden City Architecture, points out that historic Vilnius has suffered from urban fires many times. It was after the great fires of the 18th century that it was forbidden to build new wooden houses in the centre of Vilnius. Existing wooden houses were only allowed to remain if they had a neat stone chimney and the owners promised to cover the roof with tiles within two years.

Trends in Europe and Lithuania

In Western European cities, wooden construction also declined significantly in the 19th century. However, in the capitals and cities of Northern European countries, as in Lithuania, both individual wooden buildings and larger areas dominated by wooden architecture have survived. These include Skansen in Stockholm, Brygen in Bergen, Norway, Kalamaja in Tallinn, and the Žvėrynas district in Vilnius. The technology of wooden architecture was quite similar in the different countries, with only the elements of decoration differing. They depended on both culture and religion – whether the country was Protestant or Christian. Nowadays, it is fashionable to use laminated timber panels for sustainability purposes – a kind of renaissance in wooden construction that encourages interest in tradition and its application in modern construction. It is not surprising that this type of construction is taking place in countries that value wooden architecture, with the Scandinavians leading the way. According to the representative of ID Vilnius, it is wooden buildings that allow to preserve not only the character of individual parts of the city, but also the local building traditions as intangible heritage. Often in the wooden architecture of cities one can find unique signs of harmony between non-professional folk creativity, craftsmanship and professional architectural styles. The uniqueness of wooden architecture therefore encourages greater interest and preservation. In urban areas, this is important for the distinctiveness of local communities and the image of individual neighbourhoods. It also promotes tourism and attracts visitors.

“Most places like Skansen in Stockholm or Brygen in Bergen function as open-air museums and are heavily visited by tourists. In contrast, Vilnius’ Žvėryn and Tallinn’s Kalamaja are residential areas. Everyday life inevitably poses challenges to historic wooden architecture,” said Žekonytė. I. Užuotaitė said that cities are living organisms, so we cannot put certain areas under a glass shell and stop their development. There are examples in Europe where too strict bans in old towns have prevented the adaptation of infrastructure and people have stopped wanting to live there and businesses have not developed. Eventually, these areas turned into tourist wastelands. To prevent this from happening, we need an integral approach that allows people to live comfortably while preserving historic areas.

Fewer and fewer craftsmen

Over the last few decades, there has been an intense debate about the need to preserve not only wooden mansions, but also wooden residential buildings in urban areas. Such buildings often require specific maintenance and more complex restoration works, which require additional funding. Conflicts often arise between property owners and the authorities in charge of protecting the heritage site. According to Užuotaitė, the Scandinavians have long understood that their architectural identity is strongly linked to the tree, so they no longer have questions about how and what to protect. So, for example, many Norwegians in the capital Oslo live in wooden houses, whereas in Vilnius this is already a rarity. “However, even Norway, which has the means to preserve or restore such houses, faces a shortage of skilled craftsmen: they need to understand not only the construction of the house, but also the intricacies of restoring wooden buildings. Young people do not choose such specialities. We have a lot to focus on when it comes to maintaining wooden architecture, but we also need to take into account the threats that will arise in the near future,” said I. Užuotaitė.

What direction should cities take?

The neglect and loss of wooden heritage is the result of negative attitudes and the perception that they are unstable, not durable buildings. Nowadays, opinions are changing and wooden architecture is becoming prestigious. “Vilnius wooden architecture is considered valuable not only in the context of Lithuania’s heritage, but also in the context of European heritage. Hundreds of wooden buildings have survived in the central part of the city. Most of them are concentrated in the historic suburbs and other districts adjacent to the Old Town, such as Žvėryn, Šnipiškės, Antakalnis, Rasa, Užupis and elsewhere,” said M. Žekonytė. Big cities are constantly growing, which encourages the search for new ways to preserve at least some of the signs that represent their historical development. “Wooden buildings concentrated in city centres have to cope with the neighbourhood of modern high-rise buildings. However, everything can be reconciled – this is how traditional and modern architecture interact,” said the Head of Territorial Planning and Sustainable Environment at ID Vilnius.

According to Žekonytė, in some cases individual wooden buildings are seen more as relics of the past, doomed to disappear. On the other hand, they have the potential to become exceptional objects that diversify and complement the identity of cities. Entire districts of wooden architecture with a coherent cityscape are less controversial, as they do not seem to raise questions about what to do with such buildings. Their protection and maintenance can be carried out in accordance with Cultural Heritage or other documents coordinating urban development. The symbiosis between the historic and the new city is not only problematic but also a platform of exceptional opportunities. In the world’s major cities, we can see very contrasting cases of traditional low-rise and modern high-rise architecture. In Vilnius, for example, the Krokuvos Street environment at the foot of the skyscrapers in the Šnipiškės district is a case in point, with a character that is striking not only to Lithuanians but also to foreign tourists. “Krokuva Street juxtaposes the abundance of detail of traditional wooden building forms with the sterility of modern commercial architecture. However, it is difficult to answer the question of what should dominate: there is a lot of discussion about this and probably more in the future,” said Žekonytė. According to Užuotaitė, in Šnipiškės it is important to preserve not only the individual buildings but also the “village in the city”, because the network of streets, together with the low-rise buildings, helps to create a cosy feeling. These are architectural solutions from the 19th and early 20th centuries, showing that the city was multifaceted, with different people living there. Žvėrynas is interesting because it is a district that was formed in one historical period – the early 20th century. It has always been prestigious, with summer houses and villas dominating the systematically planned street network. It is like going to the countryside for a holiday.

What should local government do?

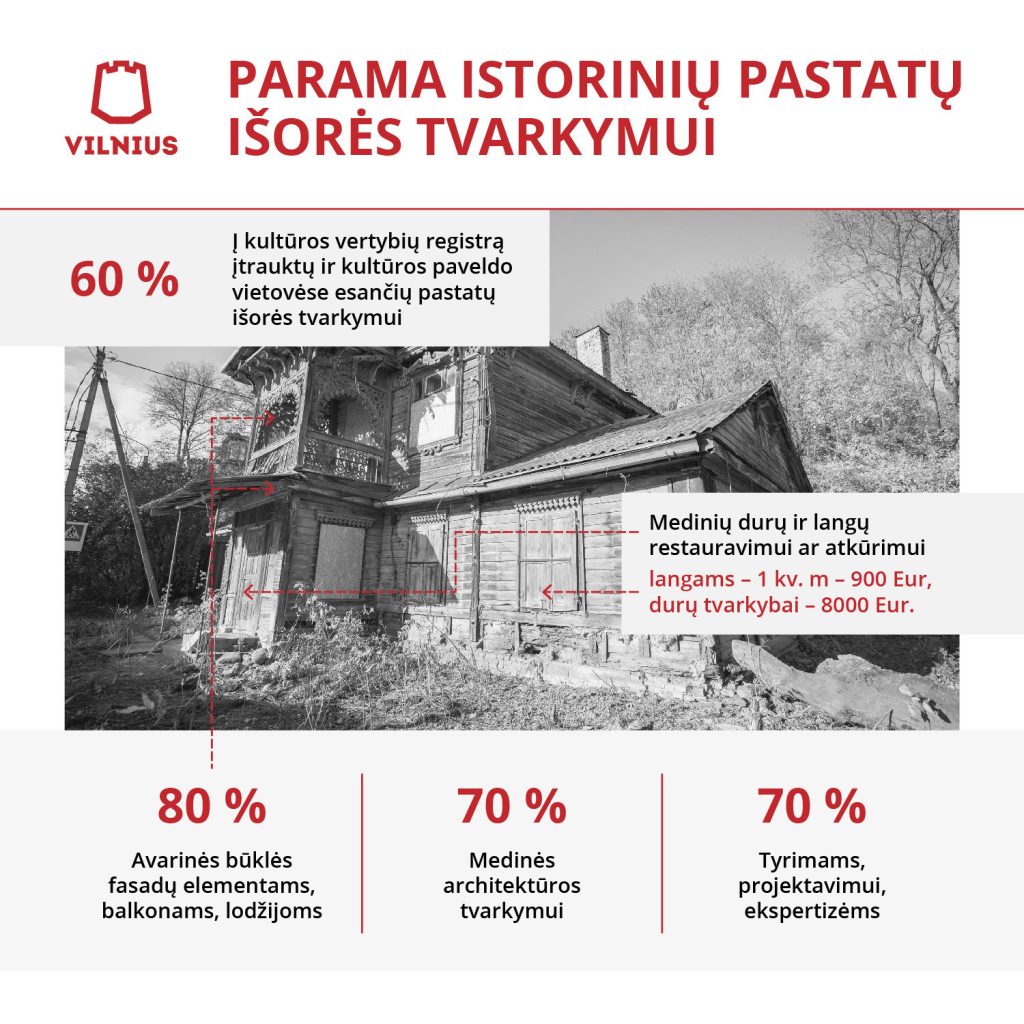

It is clear that preserving and nurturing the rather fragile wooden architecture in cities requires specific preparations. In this case, it is not only routine actions that are important, but also pro-active actions. The recently opened Museum of Wooden City Architecture is an excellent proof of the importance of wooden architecture for the city of Vilnius. According to I. Užuotaitė, the museum’s director, the protection of wooden architecture is not just about regulations and bans: communication with the population is crucial. People are not always sure what colour to paint the facade of their houses, let alone the composition of the paint. Most of the time, colours are not thought about at all, even though every city has its own colour scheme. But awareness is slowly increasing. Vilnius is continuously improving its financial support tools to ensure that as many residents as possible take advantage of the support to renovate their wooden buildings. For example, the Vilnius Old Town Renovation Agency is already accepting applications from residents for funding to renovate the exterior of culturally valuable buildings. Starting this year, up to 80% of the funding is also available for the renovation or restoration of balconies and other façade elements in a state of disrepair. Support is also available for the renovation or restoration of wooden architecture and wooden windows and doors. Owners of historic buildings in other districts, not only in the Old Town, can apply for partial funding.

Photo credit: GO Vilnius (Gabriel Khiterer) and S. Žiūros